Redefining Ownership in Digital Systems

Ownership has traditionally been defined through legal agreements, institutional records, and trusted intermediaries. In digital asset systems, ownership is defined differently, based on direct control rather than institutional recognition, shifting responsibility and authority from organizations to individuals.

The change introduced both freedom and risk. Before we delve into tools like wallets and keys, setting the stage for understanding distinguishes this definition of ownership from the more familiar financial models and explains why it matters in practice.

Ownership as Control Rather Than Permission

In traditional finance, ownership often means having permissioned access. A bank account holder owns the funds in theory, but the bank controls the infrastructure that allows those funds to move. Transactions depend on approval systems, internal ledgers, and compliance checks. Ownership exists within a framework of rules enforced by institutions.

Digital assets operate differently. Ownership is defined by control over the credentials that authorize transactions. If you can sign a transaction using the correct cryptographic key, the network recognizes you as the owner. No external approval is required. This turns ownership into a functional reality rather than a contractual promise.

The Absence of Central Registries

Another shift lies in how ownership records are maintained. Traditional systems rely on centralized registries. Banks, land offices, or brokerage firms maintain official records of who owns what. These records can be corrected, reversed, or overridden by authorities under certain conditions.

In decentralized networks, ownership is recorded on distributed ledgers maintained by many independent participants. There is no single authority that can unilaterally alter ownership records. This makes the system more resistant to arbitrary changes but also removes safety nets that people often take for granted.

Why Ownership Feels Different to Users

Because digital ownership lacks familiar intermediaries, it can feel abstract or fragile. There is no customer service desk that can restore access if something goes wrong. This creates a psychological gap between legal ownership and technical control, especially for users new to the space.

Over time, users learn that digital ownership is less about recognition and more about responsibility. Control feels empowering, but it also demands careful handling of access credentials and a clear understanding of how systems work.

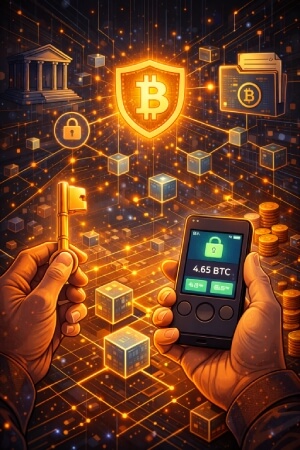

Cryptographic Keys as Proof of Ownership

At the very heart is cryptography of digital asset ownership. Instead of names, signatures, or account numbers, proof of ownership derives from mathematical keys that allow users to authorize transactions and demonstrate control, without revealing personal identity.

A proper understanding of how cryptographic keys work goes a long way into making one see why losing the access to them is tantamount to losing full possession; keeping these keys thus becomes an automatic necessity for all responsible participation in crypto systems.

Public and Private Keys Explained

Digital ownership relies on pairs of cryptographic keys. A public key acts as an address others can see and send assets to. A private key is secret and allows the owner to authorize transactions from that address. The two are mathematically linked but cannot be derived from one another.

Possession of the private key is what matters. The network does not care who you are or why you are transacting. It only verifies whether the correct cryptographic signature accompanies a transaction. This simple rule underpins the entire ownership model.

Why Keys Replace Identity

In traditional systems, identity plays a central role. Accounts are tied to names, documents, and personal data. Digital asset systems replace identity with cryptographic proof. The network does not need to know who owns an asset, only that the transaction is valid.

This design improves privacy and reduces reliance on centralized data stores. However, it also means there is no built-in recovery mechanism tied to identity. If a key is lost or compromised, the system has no way to distinguish legitimate owners from attackers.

The Finality of Key-Based Control

Key-based ownership introduces finality. Transactions, once confirmed, cannot be reversed by appealing to an authority. This reduces fraud in some cases but increases the consequences of mistakes. Sending assets to the wrong address or exposing a private key can result in permanent loss.

This finality is not a flaw but a design choice. It prioritizes certainty and resistance to manipulation over flexibility. Users must adjust their expectations accordingly.

Self-Managed Wallets and Direct Ownership

Wallets are the fundamental tools that people use to keep digital assets. Even though they are called wallets, they do not really store assets. Instead, they store keys and provide interfaces that are used to interact with blockchain networks. The management of a wallet decides who has actual ownership over the assets connected to it.

A self-managed wallet places the control directly in the hands of the user. This section looks at what that actually means according to real-world practicalities and distinguishes such ownership means from custodial arrangements.

What a Wallet Actually Does

A wallet generates and stores cryptographic keys, then uses those keys to sign transactions. It also displays balances by reading data from the blockchain. The assets themselves remain on the network, governed by the rules of the protocol.

Because wallets manage access rather than storage, losing a wallet device does not necessarily mean losing assets, as long as the recovery information is preserved. Conversely, exposing recovery information can allow others to take control regardless of physical possession.

Custodial Versus Self-Custodied Wallets

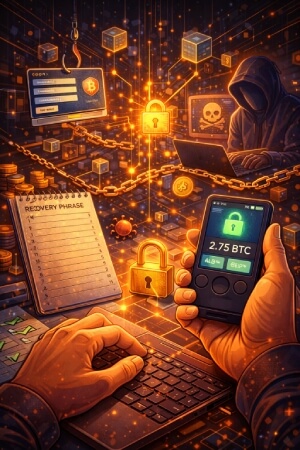

Custodial wallets are managed by third parties, such as exchanges or service providers. Users access their assets through accounts protected by passwords and support systems. While convenient, this setup means the provider controls the private keys.

Self-custodied wallets remove intermediaries. The user generates and controls the keys directly. This grants full ownership but also removes external protections. There is no account reset or dispute resolution process if access is lost.

The Responsibility Shift to the User

Self-managed ownership shifts responsibility entirely to the individual. Security practices, backups, and access management become personal duties rather than services. This can be empowering for experienced users and overwhelming for newcomers.

The trade-off is clear. Greater control comes with greater accountability. Understanding this balance helps users choose the right custody model for their needs.

How Digital Ownership Differs From Traditional Finance

Digital asset ownership challenges many assumptions built into traditional financial systems. These differences affect not just how assets are held, but how trust, risk, and accountability are distributed across the system.

Recognizing these contrasts helps clarify why digital ownership can feel unfamiliar and why existing legal and regulatory frameworks sometimes struggle to accommodate it.

Intermediaries and Trust Models

Traditional finance relies heavily on intermediaries to manage trust. Banks, clearinghouses, and custodians verify transactions, maintain records, and absorb certain risks. Users trust these institutions to act correctly and resolve disputes.

Digital asset systems reduce reliance on intermediaries by embedding rules directly into protocols. Trust shifts from organizations to code and cryptography. This reduces some risks while introducing new ones related to software and user behavior.

Reversibility and Consumer Protection

Many traditional systems allow transactions to be reversed or disputed. Chargebacks, freezes, and court orders provide mechanisms for correcting errors or addressing fraud. These protections are part of the service model.

Digital ownership generally lacks such mechanisms. Transactions are designed to be final. While this reduces ambiguity, it also removes safety nets. Users must rely on prevention rather than remediation.

Legal Recognition Versus Technical Reality

In traditional finance, legal recognition defines ownership. Courts and regulators can enforce claims even if technical systems fail. In digital systems, technical control often precedes legal interpretation.

This creates tension. A person may be legally entitled to an asset but unable to access it without the correct key. As laws evolve, this gap remains a defining feature of digital ownership.

Security, Risk, and Personal Accountability

Owning digital assets securely requires an active approach to risk management. Without intermediaries to absorb losses or correct errors, individuals must think carefully about how they protect access credentials and interact with networks.

Security is not just a technical issue. It is a behavioral one, shaped by habits, awareness, and decision-making under pressure.

Common Risks in Digital Ownership

The most common risks include phishing attacks, malware, and accidental disclosure of private keys. Social engineering often plays a larger role than technical exploits, targeting users rather than systems.

Another risk is simple human error. Misplacing recovery phrases, using insecure devices, or misunderstanding transaction details can all result in loss. These risks highlight the need for education and cautious practices.

Backup and Recovery Practices

Effective ownership includes planning for failure. Secure backups of recovery information are essential. These backups should be protected from both theft and accidental destruction.

Balancing accessibility and security is challenging. Too much convenience increases exposure, while excessive secrecy can lead to loss. Thoughtful backup strategies reflect an understanding of this balance.

The Role of Education and Awareness

As digital ownership becomes more common, education becomes a form of protection. Understanding how systems work reduces reliance on guesswork and misplaced trust.

Clear explanations, realistic expectations, and honest discussions about risk help users make informed decisions. Ownership without understanding is fragile, regardless of the technology involved.

Practical Implications of Owning Digital Assets

Digital ownership affects more than individual transactions. It shapes how people think about value, responsibility, and participation in economic systems. These implications extend beyond crypto markets into broader discussions about digital rights and autonomy.

Before concluding, it is useful to summarize how these ideas translate into everyday decisions and behaviors.

- Direct ownership requires managing access credentials personally

- Loss of keys usually means loss of assets

- Control replaces permission as the basis of ownership

- Security practices are part of ownership, not optional extras

- Convenience often trades off against control

These points influence how users choose wallets, platforms, and security measures. They also shape expectations about support, recovery, and accountability in digital systems.

Ownership as Responsibility

Having digital assets is a commitment towards holding more than only a digital representation of value on a screen. It signifies controlling access through cryptographic keys and rigorously accepting the responsibilities a holder must reside with. Even without the establishment to fall back on, the owner stands naked before the object of asset. Being grounded between the owner and the asset overlooks the prime advantage: independence demanding care, insight, and self-discipline. As digital assets escalate in significance, clear thinking concerning ownership remains one of the pivotal skills a participant may develop.